Ludwig Guttmann

As the London Paralympics draws to a close, what do you know about the man who created them, and how he came to do it? Unsurprisingly, he was a doctor, but not just any doctor.

Ludwig Guttmann

The Paralympics grew out of the Stoke Mandeville Games for the Paralysed, which were held at Stoke Mandeville Hospital in 1948. This was a humble affair, an archery competition with 16 competitors: 14 men and just 2 women. It was the brainchild of Ludwig Guttmann. Who was?

His biography was published in 1986. Written by Susan Goodman, it has a Foreword by Prince Charles, who writes “It is amazing to think that not many years ago the treatment of paraplegics was generally regarded as a waste of time. In those days some eighty per cent of people who sustained spinal cord injuries were dead within three years. Today their life expectancy is normal”.

Ludwig Guttmann was both German and a Jew by birth; born July 3, 1899, he entered the University of Breslau on April 1, 1918 where he studied medicine, but nearly didn’t live to. Between 1918 and 1920, the Plague of the Spanish Lady swept across the globe killing more people than the Great War. Guttmann contracted this insidious strain of influenza, and nearly died of it, but fortunately for both him and the world, he survived, and in 1924 completed a thesis on tracheal tumours passing his MD.

By the mid-1930s he was already a distinguished neurologist and neurosurgeon, but the government of a certain Herr Hitler was not impressed, and on March 14, 1939 he arrived at Dover from France with his family, and 40 Marks in his pocket.

He soon took up a post as Research Fellow at the Nuffield Department of Neurosurgery in the Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford, and in 1943 he moved to the Stoke Mandeville Hospital, Buckinghamshire, where he took charge of the new National Spinal Injuries Centre. As might be expected, many of his patients were young men who had been crippled in the ongoing Second World War.

Although he is remembered principally for founding the paralympics and also for his considerable contributions to neurology, his greatest achievement appears to be one of those simple things science tends to overlook.

The two biggest dangers for paraplegic patients are pressure sores and urinary infections; from the beginning of his appointment at Stoke Mandeville, Guttmann tackled these by ensuring that patients were turned regularly and that urine bottles were emptied, he also ensured his charges were catheterised professionally.

Although Prince Charles was wrong when he said paraplegics now have a normal life expectancy, it is undoubtedly true that without Guttmann’s pioneering methodology, paraplegics worldwide would enjoy not only considerably shorter lives but considerably less quality of life.

Guttmann has been called an authoritarian, which is not a trait one would expect in a refugee from Nazi Germany, but unlike government, there is no virtue in democratic medicine; patients who are suffering from serious infections, injuries or both need to follow competent medical advice, not vote on it. People who suffer life changing injuries also need self-discipline to deal with the many problems they will face for the rest of their time on this Earth, and discipline to instill self-discipline is part of this rehabilitation.

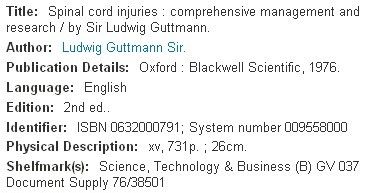

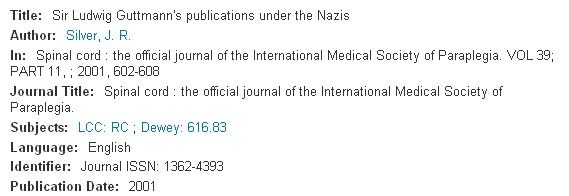

Like all leading medical men, Guttmann published a considerable body of scientific literature – see for example the two pictures below. In 1976, he also produced the Textbook of Sport for the Disabled, by which time he was Sir Ludwig Guttmann; he received his knighthood in 1966 having become a British citizen in 1945.

This book includes chapters on wheelchair sports, sports for amputees, the blind and partially sighted, cerebral palsy sufferers and the deaf. His aforementioned biography is rightly called SPIRIT OF STOKE MANDEVILLE The Story of Sir Ludwig Guttmann.

Sir Ludwig Guttmann died March 18, 1980, but his name is known more widely today than ever. He is remembered through the annual Sir Ludwig Guttmann Lecture, a recently unveiled statue, and most of all through the four yearly Paralympics.

[The above article was first published September 8, 2012.]

Back To Digital Journal Index

A screengrab from the British Library catalogue.

A screengrab from the British Library catalogue.